Logical Fallacies: Recognizing and Avoiding Missteps in Debate

Logical fallacies are mistakes in reasoning that can undermine arguments, and they’re commonly encountered in debates, discussions, and speeches.

Understanding logical fallacies is essential for crafting persuasive arguments and recognizing flawed reasoning from others.

Being aware of these fallacies can elevate a delegate’s ability to debate effectively, propose solutions, and maintain credibility in the eyes of fellow delegates. This guide will introduce the concept of logical fallacies, explore some of the most common types, and show you how to fight back.

What Are Logical Fallacies?

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that weaken arguments. They can occur in various forms, often distracting from the core issues or presenting inaccurate conclusions.

In MUN, fallacies might arise when delegates become overly emotional, use misleading statistics, or make hasty generalizations. Identifying these fallacies is crucial for MUN delegates and will help you in any debate.

Check out our guide on Debate Skills here!

Common instances where Logical Fallacies might pop up:

- During a delegates speech in a Moderated Caucus

- During an Unmoderated Caucus discussion

- During a Q&A Session.

Common Logical Fallacies

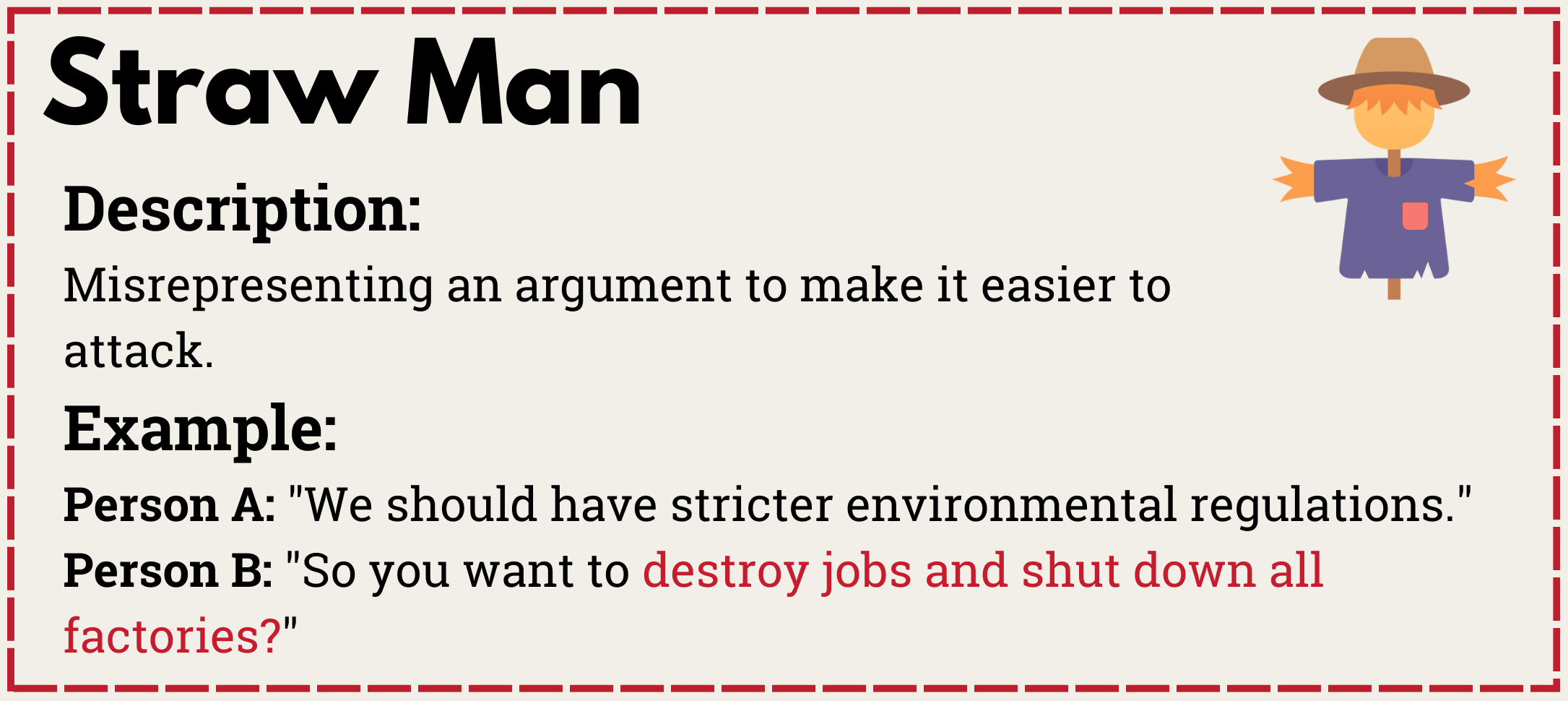

Straw Man Argument

- The Mistake: This fallacy involves misrepresenting an opponent’s position to make it easier to attack.

- In MUN: During debates, a delegate may oversimplify or exaggerate another country’s stance to discredit it. For instance, if a delegate from one country suggests a slight increase in aid to developing nations, another delegate might respond by accusing them of wanting to give away unlimited resources, misrepresenting the original suggestion. This not only weakens the debate but also distracts from constructive discussion.

- How to Avoid: Instead of exaggerating or distorting others' positions, summarize their arguments fairly before presenting counterpoints.

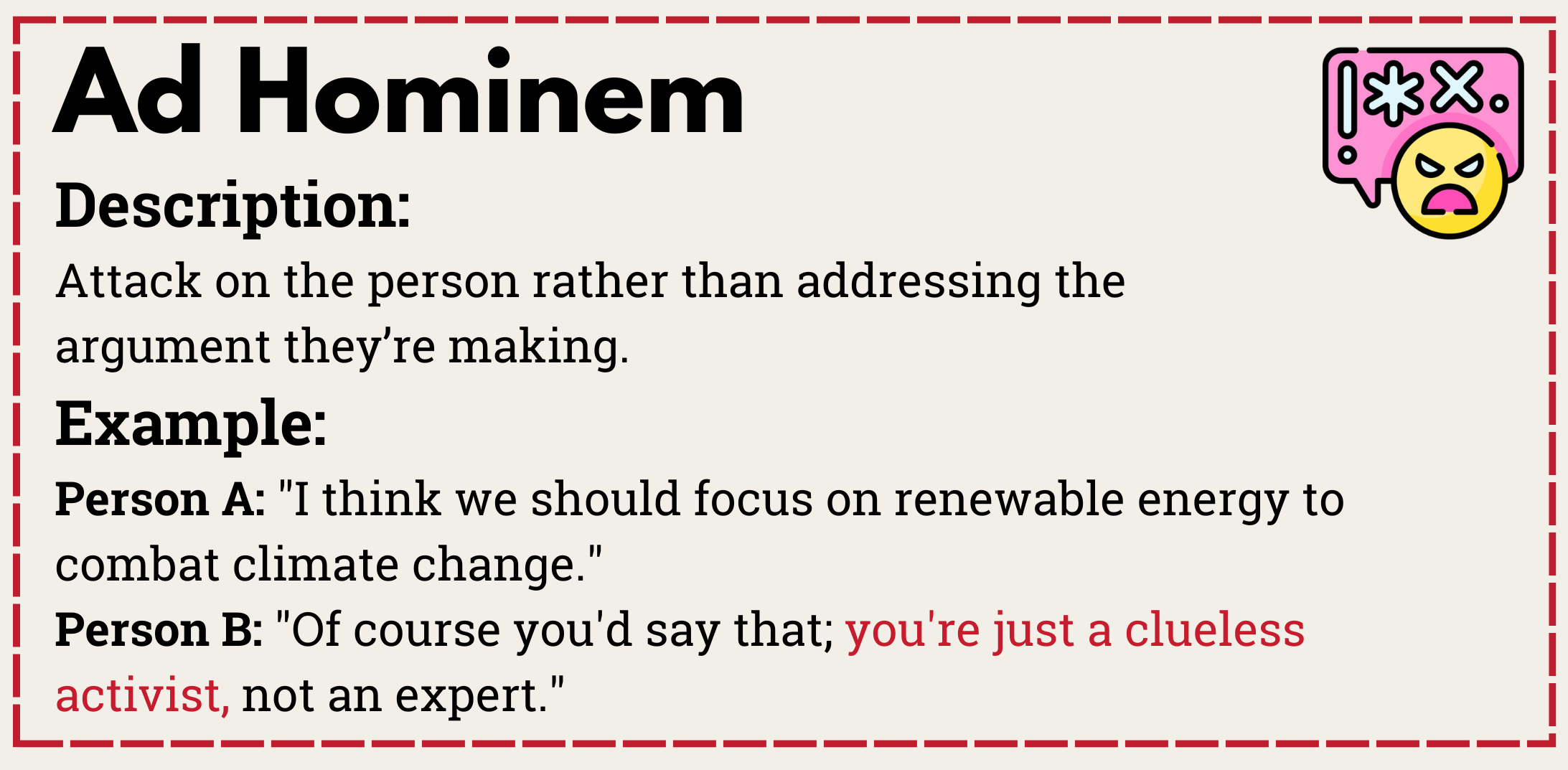

Ad Hominem Attack

- The Mistake: This is an attack on the person rather than addressing the argument they’re making.

- In MUN: When discussions become heated, it can be tempting to question the credibility or character of another delegate, especially if they represent a country with a controversial record. For example, saying, “Of course they would oppose this resolution—they’re from [country with controversial policies]” is an ad hominem attack that deflects from the real issue.

- How to Avoid: Focus on the ideas, not the individual. In MUN, it’s critical to maintain a diplomatic approach, addressing the substance of arguments without veering into personal attacks.

Slippery Slope

- The Mistake: This fallacy suggests that one small step will inevitably lead to a chain of related events, usually with negative outcomes.

- In MUN: A delegate might argue, “If we allow this resolution on renewable energy, soon every country will be forced to abandon fossil fuels entirely.” While it’s crucial to consider potential consequences, the slippery slope fallacy exaggerates the likelihood of extreme outcomes. It’s a flawed tactic that shifts the focus from practical policy decisions to hypothetical worst-case scenarios.

- How to Avoid: Base arguments on evidence and probabilities, not on alarmist projections. When raising concerns, consider whether they are likely and relevant to the current resolution.

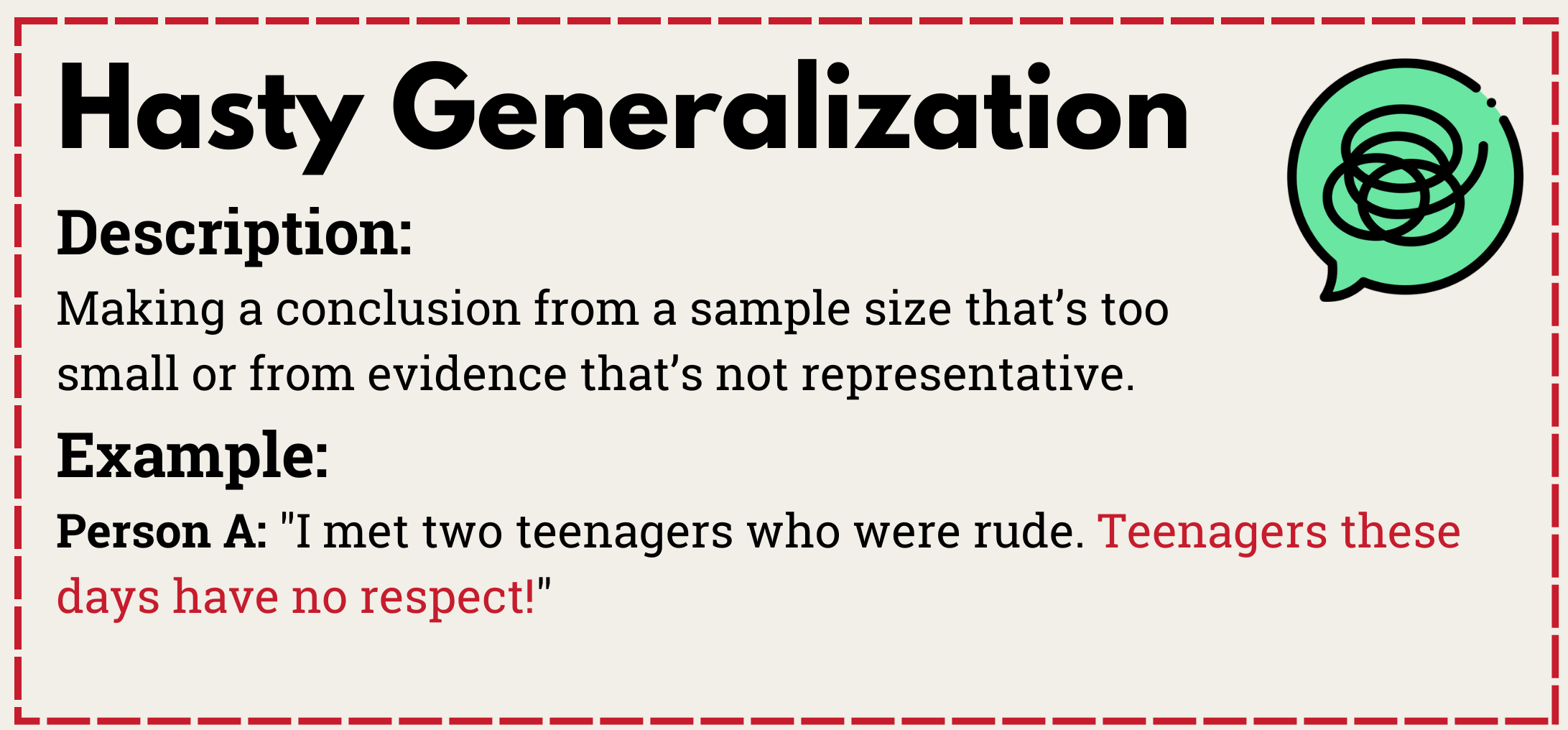

Hasty Generalization

- The Mistake: This fallacy occurs when a conclusion is drawn from a sample size that’s too small or from evidence that’s not representative.

- In MUN: A delegate might say, “I’ve seen that one developed nation is supporting this measure, so all developed nations must support it.” This hasty generalization assumes that a single example represents the whole, which may not be accurate. In MUN, relying on such assumptions can lead to flawed strategies and diminish the delegate’s credibility.

- How to Avoid: Seek out comprehensive data and avoid making assumptions based on isolated examples. Present well-rounded evidence to support your position.

Appeal to Emotion

- The Mistake: This fallacy attempts to manipulate an emotional response in place of a valid argument.

- In MUN: While emotion can be a powerful tool, over-reliance on emotional appeals can backfire. For example, a delegate might overemphasize the tragic consequences of a humanitarian issue to the point of ignoring viable solutions or practical constraints. Emotional appeals are often paired with other fallacies, such as appealing to pity, which can cloud the debate and lead to an unfocused resolution.

- How to Avoid: Balance emotional appeals with rational arguments. It’s entirely appropriate to acknowledge the human impact of issues, but it’s important to anchor arguments in logic and practicality to maintain a persuasive stance.

Why Avoid Logical Fallacies?

Logical fallacies can have a detrimental impact on your position within MUN. First, they can weaken your credibility. Delegates who rely on solid evidence and well-reasoned arguments are often seen as more trustworthy and are more likely to gain allies. Logical fallacies, on the other hand, may indicate to others that you are avoiding critical engagement with the topic.

Logical fallacies also lead to ineffective resolutions. If a resolution is based on faulty reasoning, it’s unlikely to address the root causes of the issue effectively. For example, a resolution born from a slippery slope argument may try to preempt unlikely scenarios rather than solve immediate problems. Ensuring that arguments are logical, sound, and evidence-based can lead to more practical and impactful resolutions.

Recognizing and Responding to Logical Fallacies

In MUN, recognizing fallacies in others’ arguments allows you to respond more effectively. Here are some steps to address logical fallacies during debate:

- Identify and Clarify – Politely point out the fallacy, if appropriate, and explain why it doesn’t align with the issue at hand. For instance, if a delegate uses a hasty generalization, suggest that more comprehensive data may be needed.

- Redirect to the Core Issue – Avoid getting sidetracked by a fallacy. If someone uses a straw man argument, acknowledge the misrepresentation and then restate your position clearly.

- Use Evidence-Based Reasoning – Support your own responses with evidence. This not only bolsters your argument but also demonstrates a commitment to logical and thorough debate.

Learn more about dealing with logical fallacies.

Conclusion

Understanding and avoiding logical fallacies is an essential skill for MUN delegates who wish to present strong, well-founded arguments. By remaining vigilant for fallacies in your own reasoning and in others’, you can contribute to a more productive and respectful debate. Logical clarity helps not only in persuading others but also in crafting resolutions that are realistic, feasible, and impactful. Remember, MUN is a platform for diplomacy and critical thinking, and recognizing logical fallacies will enable you to become a more effective and respected delegate.